|

The era of Antiquity 1830 - 1845 The era of Antiquity can be seen as the era of calculator

devices that had no memory, but features like output devices as well

as some kind of data storage becomes common.

Larger and more over general purpose machines analogous to that of Babbage will be constructed. The first idea of a computer is created by Babbage, be it only on paper. But the idea is there! What bothers scientists now are the limited mechanical possibilities of machinery |

pre history | antiquity

| pre industrial era | industrial

era

1620 -

1672 - 1773 - 1810

- 1830 - 1846 -

1874

|

|

|

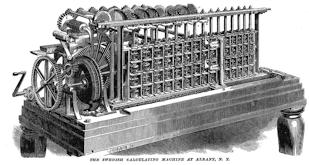

![]() Georg en Edvard Scheutz (Sweden)

- father and son - after reading Babbage's article on his machine, start to

develop a Difference Engine themselves. They are the persons that created the

first machine that could print mechanically(!) calculated tables. The machine

will be finished in 1843.

Georg en Edvard Scheutz (Sweden)

- father and son - after reading Babbage's article on his machine, start to

develop a Difference Engine themselves. They are the persons that created the

first machine that could print mechanically(!) calculated tables. The machine

will be finished in 1843.

The design is less robust and the tolerances(14) larger than those strove for by Babbage. For us, this raises the question if Babbage's tight tolerances were really needed.

The problem of reproducing results without human errors as meant by Babbage is solved: the numbers are printed on paper maché or soft metal strips (tin of lead). These strips are used to make clichés for the reproduction of the tables.

At the same time Babbage shifts his attention to the Analytical Engine. One that closely resembles the architecture of 21st century computers.

![]() It was at this point, 1834,

that Babbage had an idea for a completely

It was at this point, 1834,

that Babbage had an idea for a completely

different machine - one that would operate more rapidly and have far more

possibilities than the Difference Engine.

Four basic elements are considered here:

- Input unit

- The ALU or Algorithmic Unit

- Central controller

- Output unit

With his experience from the difference engine, he knows that to build such

a machine funding from his private funds is necessary. He succeeds in

building a small model of the Analytical Engine.

He asked the government whether he should continue with the Difference Engine

or proceed with the new machine. It was eight years before the government advised

him that regretfully they had to abandon the project.

They had spent 17,000 pounds with nothing to show. Babbage too had spent a comparable

amount of his own money.

![]() Unable to wait for the government decision, Babbage starts work

on the Analytical Engine, as the new engine

was later named. He did not expect to build this machine nor did he expect government

support. But, he did believe that a machine with its possibilities would become

a reality at a later date, perhaps based on his completed drawings. The Analytical

Engine was really the GRAND VISION.

Unable to wait for the government decision, Babbage starts work

on the Analytical Engine, as the new engine

was later named. He did not expect to build this machine nor did he expect government

support. But, he did believe that a machine with its possibilities would become

a reality at a later date, perhaps based on his completed drawings. The Analytical

Engine was really the GRAND VISION.

It was to be capable of carrying out any mathematical operation. Instructions would tell it what operation to perform and in what order. It would have a memory with a capacity of one-thousand 50-digit numbers, it would draw on auxiliary functions such as logarithm tables (of which it would possess its own library) and subroutines. It would also compare numbers and act upon its judgments, thus proceeding along lines not uniquely specified in advance by the instructions.

All of these functions sound familiar since they are an integral part of modern computers. But Babbage was attempting to carry them out mechanically with no help from electrical circuits or electronic means.

He called his central processing unit the mill. The separate storage area, the store.

![]() The vision continued with plans

to use punched cards to control the engine, an idea

Babbage had learned from Joseph Jacquard, who had used punched cards to control

his automatic loom early in the century. One set of cards would program the

mill, telling it which operation to perform. Another set would store the numbers

to be acted upon.

The vision continued with plans

to use punched cards to control the engine, an idea

Babbage had learned from Joseph Jacquard, who had used punched cards to control

his automatic loom early in the century. One set of cards would program the

mill, telling it which operation to perform. Another set would store the numbers

to be acted upon.

![]() The introduction of punched cards

ascertained Babbage's feeling that he had invented something really new, something

more than just a sophisticated calculating machine.

The introduction of punched cards

ascertained Babbage's feeling that he had invented something really new, something

more than just a sophisticated calculating machine.

He wrote in his notebook on July 10, 1836, "This day I had for the first time a general but very distinct conception of the possibility of making an engine work out of algebraic development." Babbage had on paper completed of what is today "the general purpose digital computer."

Few people understood Babbage's work or realized its significance.

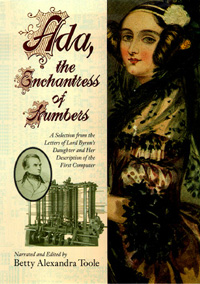

![]() One remarkable exception was Countess

Ada Augusta Lovelace, the only legitimate

daughter of Lord Byron. A mathematician in her own

right, she worked closely with Babbage, planned his computational problems,

and has been called the world's first programmer.

She translated an article on the Analytical Engine written in Italian by L.

F. Menebrea, adding her own lengthy notes on the machine

and its potential. This is the most important written work on the subject.

One remarkable exception was Countess

Ada Augusta Lovelace, the only legitimate

daughter of Lord Byron. A mathematician in her own

right, she worked closely with Babbage, planned his computational problems,

and has been called the world's first programmer.

She translated an article on the Analytical Engine written in Italian by L.

F. Menebrea, adding her own lengthy notes on the machine

and its potential. This is the most important written work on the subject.

Babbage never completed his engines. But his son, Henry, spent some time later in his life working on the Analytical Engine. The assembled pieces of this machine along with the unfinished portion of the Difference Engine are at the Science Museum, London. Replicas are in the IBM collection.

Most of Babbage's contemporaries thought he was an eccentric dreamer obsessed with a slightly mad vision. Even those who tried to understand conceded only that his engine was an interesting theoretical possibility. However, looking back from this age of the computer, Babbage looks quite different.

He is seen as an unheralded prophet of the modern era, an impractical genius who could not reconcile the grandeur of his vision with the technological capabilities of his own age, and who therefore wasted most of his talents.

![]() Joseph Henry invents the electrical

relay, a means to send electrical pulses over great distances. The foundation

for the telegraph is laid.

Joseph Henry invents the electrical

relay, a means to send electrical pulses over great distances. The foundation

for the telegraph is laid.

|

Bernoulli numbers were introduced in the 17th century and are forming a mathematical irregular sequence: B1 = -1/2, B2 = 1/6, B3 = 0, B4 = -1/30 ... Bernoulli numbers can be used to calculate the sum of squares of whole numbers. This technique will be used to crack codes in later centuries. |

![]() The British physicist and inventor Sir Charles

Wheatstone and the British electrical engineer Sir William

Fothergill Cooke invent the first British

electric telegraph. (Sir Charles was a busy man. Amongst other things, he also

invented the accordion in 1829 and three-dimensional photographs in the form

of his stereoscope in 1838.)

The British physicist and inventor Sir Charles

Wheatstone and the British electrical engineer Sir William

Fothergill Cooke invent the first British

electric telegraph. (Sir Charles was a busy man. Amongst other things, he also

invented the accordion in 1829 and three-dimensional photographs in the form

of his stereoscope in 1838.)

![]() Samuel Finley Breese Morse

patents a more practical version of the telegraph.

Samuel Finley Breese Morse

patents a more practical version of the telegraph.

(23)

(23)

This one sends codes in combinations of short and long pulses: dots and strokes.

He demonstrates the construction together with Alfred Vall(15) . In 1844 the first connection between two cities (Washington and Baltimore) will be realized.(16)

|

Thomas Fowler invents a calculating machine, built in wood, that was much admired by his contemporaries Augustus De Morgan, Charles Babbage, George Airey and many others. The machine used a tertiary calculating model.(24) At right is a reproduction made by Glusker and Vass

|

|

![]() Ada

Lovelace (1816 - 1852), after her translation of an article of the Italian

Luigi F. Menabrea (1809 - 1896) about the Analytical

Engine of Charles Babbage, designs some of the first examples of a computer

programs. It will take almost a century before her work is rediscovered and

the importance of it is realized.

Ada

Lovelace (1816 - 1852), after her translation of an article of the Italian

Luigi F. Menabrea (1809 - 1896) about the Analytical

Engine of Charles Babbage, designs some of the first examples of a computer

programs. It will take almost a century before her work is rediscovered and

the importance of it is realized.

In this age women were not supposed to do anything else than being well mannered

and bear children. Some of the famous works from women are published under a

pseudonym (George Sand) or under the personal name of their husband (e.g. Brahms)

in order to have their work published.

From a mathematical viewpoint, Lovelace was not satisfied with her translation. Nothing about the mathematical principles that laid the basis for the Analytical Engine was taught. Also about the possibilities of the Engine nothing was written. This prompted her to write the famous "Seven Notes" (A through G) in addition to the article. These notes were of importance because they describe the future possibilities of a computer.

To clarify her argumentation she writes a program to calculate the numbers

of (Jakob) Bernoulli (Swiss).

It takes until 1953 before these notes are rediscovered and the importance is

recognized. The Department of Defense (USA) commemorated her and named a programming

language after her: ADA.(17)

![]() In this year the principle of the Fax (Facsimile)

is invented, nicknamed the "recording telegraph". The Scottish physicist

Alexander Bain

will obtain a patent for his work. A marketable device however will not be sold

until 1861 by Giovanni Casselli.(18)

In this year the principle of the Fax (Facsimile)

is invented, nicknamed the "recording telegraph". The Scottish physicist

Alexander Bain

will obtain a patent for his work. A marketable device however will not be sold

until 1861 by Giovanni Casselli.(18)

Fax is short for Facsimile and is a device that can transmit an image by electronic

signals to another similar device. Other brands and flavors are at this time

incompatible with one another.

Transmission via telephone lines will take another 92 years to happen. Graham

Bell, in 1869, invents the telephone, and only in 1935

the first fax will transmit its signal via a telephone line.

![]() Babbage's Difference Engine did

contribute to a successful venture: it inspires a Swedish printer, George

Scheutz, to build his own engine to calculate differences and print tables.

He and his son Edward accomplish this in 1843. They built two machines. One

went to the Dudley Observatory at Albany, New York. The other to the Register

General at Somerset House in England. These two machines are at the Smithsonian

and the Science Museums. IBM has a replica in its collection.

Babbage's Difference Engine did

contribute to a successful venture: it inspires a Swedish printer, George

Scheutz, to build his own engine to calculate differences and print tables.

He and his son Edward accomplish this in 1843. They built two machines. One

went to the Dudley Observatory at Albany, New York. The other to the Register

General at Somerset House in England. These two machines are at the Smithsonian

and the Science Museums. IBM has a replica in its collection.

![]() Returning to the path that led to commercial calculators: one of

the beginnings of commercial calculators coincides with the typewriter: the

keyboard, derived from musical instruments. Considerable ingenuity was required

to make this work effectively.(23)

Returning to the path that led to commercial calculators: one of

the beginnings of commercial calculators coincides with the typewriter: the

keyboard, derived from musical instruments. Considerable ingenuity was required

to make this work effectively.(23)

Once Morse convinced Congress to sanction the first long-distance telegraph line, an iron wire was strung between posts from Baltimore, Maryland to Washington, D.C. -- a distance of 37 miles. On May 24, 1844, the first telegraph message, "What hath God wrought," was successfully sent and received along the first telegraph wire system.(1)

| Last update 24 February, 2004 | For suggestions please mail the editors |

Footnotes & References